Aleppo’s Quiet Exodus

How the Kurds Disappear Between Headlines

The news, lately, has the moral attention span of a drunken juror. It stumbles from exhibit to exhibit, swearing each one is the key to the case, then wandering off to the corridor in search of a stronger drink.

On January 12, 2026, the corridor is crowded. Venezuela supplies the operatic spectacle: a strongman’s entourage, a courtroom calendar, a Washington press line, a country’s tragedy compressed into a headline that can be consumed between two subway stops. Russia provides the maritime farce: a “shadow fleet” that behaves like a pirate flotilla wearing legal makeup, with seizures and pursuits that read like a briefing written by Tom Clancy’s accountant. Iran delivers the most consequential drama of all, the oldest script in the region performed by the bravest cast: ordinary people stepping into the street to demand a normal life from a regime built to prevent one. Then there is Greenland, a slab of ice dragged into the warm theater lights by a man who understands that geopolitics, like show business, rewards the performer who refuses to leave the stage.

All of this is real, in varying degrees. All of it matters. All of it has the crispness that editors love: flags, villains, speeches, maps that can be colored in.

Meanwhile, a far less theatrical event unfolds in Aleppo, and the world yawns.

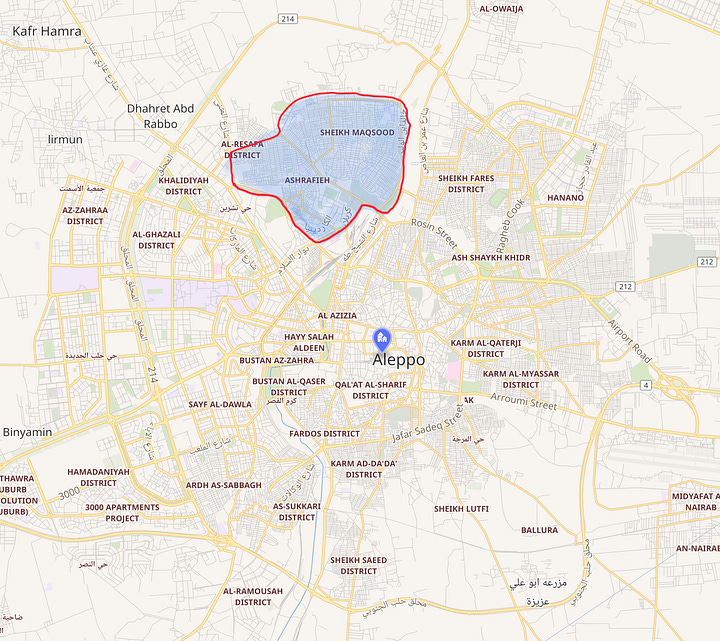

In the north quarters of that ruined, stubborn city, Kurdish neighborhoods have again become a proving ground for a regional habit: squeeze the minority until it learns the vocabulary of disappearance. In early January, fighting and shelling sent waves of families out of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyah, carrying the essentials of a life into plastic bags and the rest into memory. The numbers climbed fast enough to make any serious person sit up. The response in the West was a half-lidded glance, the sort reserved for weather reports in countries one does not plan to visit.

There is a particular cruelty to Kurdish history that deserves its own genre. The Kurds are forever being praised in the past tense. When the Islamic State rose like a medieval fever and declared itself a caliphate with a social media team, Kurdish fighters became the West’s favorite on-screen allies. They did the grinding, close-quarters work that air power cannot do. They bled on ground the coalition preferred to survey from altitude. Their dead were treated as an inspiring statistic. Their women were photographed as symbols, an emancipatory poster campaign conducted over mass graves.

Then the camera moved on.

The relationship that formed during the ISIS years had the intimacy of comradeship and the paperwork of a subcontract. Washington spoke the language of partnership. Strategy spoke the language of limits. Kurdish communities heard the first and lived under the consequences of the second. The result is familiar: the West retains the flattering memory of having “helped,” while the Kurds inherit the geography of being helpable.

Aleppo adds a newer, uglier twist. The pressure on Kurdish autonomy no longer comes from a single direction. It comes as a convergence, a regional overlap of interests that requires no treaty signing, no summit photo, no awkward embrace between leaders who would rather spit than shake hands. Damascus wants sovereignty in the way a bankrupt landlord wants rent: immediately, forcibly, with no patience for tenants who have started governing themselves. Ankara wants Kurdish power shrunk to the smallest possible footprint, because Kurdish self-rule across the border looks like a contagion that might breach Turkey’s own walls. These two desires intersect over Kurdish neighborhoods like the blades of a pair of shears.

Behind this convergence stands a broader permission structure, the kind that grows quietly while the world debates slogans. Islamist governance is being introduced to the international stage wearing a pressed suit, speaking the language of stability, requesting sanctions relief, promising order. Ahmed al-Sharaa, a name that still carries the odor of insurgency, is treated in diplomatic reporting as a practical necessity, a transitional figure, a man to be engaged because the alternative is chaos. The logic is familiar to anyone who has watched religion’s ability to pass itself off as moderation when it acquires a ministry and a flag.

It is possible, of course, that this time really is different. It is possible that statehood will tame the worst instincts of men who once found purity in violence. It is possible that “integration,” “security,” and “normalization” will mean exactly what they say. It is also possible that these words will become the new incense: a pleasant smell used to mask the scent of coercion.

The truth of Aleppo will be decided in the dullest places. At checkpoints. In “vetting” procedures. In property offices. In the return phase, that slow bureaucratic afterlife where displacement graduates into demographic reality. The first act is always loud. The second act is always administrative. The second act is where a community learns whether it has a future, or only a past.

This is where the Kurdish story becomes the story of everybody who still imagines that liberal democracies can outsource their dirty work, pocket the moral credit, and keep their credibility intact. The bill arrives eventually. It arrives in the form of cynicism, radicalization, migration pressure, and a global lesson learned by every ambitious militia: fight the right enemy at the right time, then rebrand as governance and wait for the invitations.

So yes, the week is crowded. The headlines are loud. The stage is full of performers. That is exactly why you should pay attention to the people being pushed off it.

Because if the Kurds can vanish from the Western conscience at the very moment their displacement accelerates, then the lesson has already been taught. It will not stay in Aleppo.

THE ALLIANCE THAT DOES NOT NEED A TREATY

There is a comforting superstition in Western commentary: that history is moved by coalitions announced at podiums, by summits, by declarations solemnly read into microphones. This is the diploma disease, the belief that power only becomes real once it has stationary.

The Middle East prefers a cheaper method. It runs on convergences.

Turkey does not have to embrace Damascus to profit from Damascus tightening its fist on Kurdish districts. Damascus does not have to love Ankara to enjoy Ankara’s vocabulary of “counter-terrorism,” because that vocabulary has been tested, exported, and accepted. Rival states can cooperate without the indignity of friendship. They simply lean, at the same time, against the same door.

The result is a kind of regional physics. Kurdish autonomy becomes the weak point that multiple hands press on, each for its own reasons, each in its own language, all producing the same pressure. In one mouth it is sovereignty. In another mouth it is security. In a third it is unity. The nouns change. The boots remain.

What makes this convergence especially efficient is that it has a moral alibi built into it. The Kurdish-led forces in Syria are not a Sunday school. They are armed, disciplined, sometimes coercive. They run checkpoints. They conscript. They arrest. They govern, which is what armed movements do when they become administrations. This reality gives their enemies something invaluable: rhetorical cover. Every crackdown can be framed as an overdue restoration of order. Every mass “evacuation” can be pitched as a humanitarian measure. Every detention can be defended as a security necessity. The world, exhausted by Syria’s length and numb to its grief, has learned to accept these phrases as if they were neutral descriptions rather than political choices.

You can see the trick in miniature: first the story is “clashes.” Then it is “withdrawal.” Then it is “normalization.” Then it is “stability returns.” Somewhere between those verbs, a neighborhood empties.

This is why the most important phase is never the one with artillery. The decisive phase begins when the shooting tapers off and the paperwork comes out. The guns clear the street. The forms decide who owns it.

The Kurds have learned this lesson the hard way, repeatedly, across borders that were drawn by strangers and defended by everyone except those who live inside them. The Kurdish predicament is that they sit at the intersection of three anxieties: the state’s fear of fragmentation, the nationalist’s fear of contagion, and the theocrat’s fear of pluralism. They can be accused of being separatists by one side, heretics by another, and proxies by a third. And because the accusations contradict each other, they create an all-purpose permission slip.

Erdogan’s Turkey supplies a familiar chapter in this story. The oppression of Kurds inside Turkey has rarely needed panturkist manifestos. It has operated through the ordinary machinery of state power: prosecution, de-politicization, policing, the reduction of a minority’s civic life to a security file. Cross the border into Syria, and that logic does not vanish. It expands. It becomes foreign policy with domestic resonance: a threat kept at arm’s length, a precedent prevented, a story told to voters about defending the homeland.

Damascus supplies the other chapter. After years of civil war, nothing is more tempting to a reconstituting state than the performance of sovereignty. Sovereignty is theater and coercion at once. It means flags on buildings and men at checkpoints. It means a single chain of command, one that does not tolerate armed enclaves, however local their legitimacy may feel. And so the Kurdish districts in Aleppo become a test, not only of force, but of symbolism: can the state re-enter? can the state stay? can the state make return conditional?

Here is where the new Islamist respectability enters the plot without announcing itself. If the international system begins treating an Islamist-rooted leadership as the necessary manager of Syria’s “stability,” then every act of consolidation can be framed as part of a reassuring trajectory. The world longs for a Syria that is governable. Longing is a dangerous drug. It can make the observer confuse quiet with justice and control with legitimacy.

This is how convergences become outcomes. Not by grand conspiracies. By overlapping interests. By the slow learning of a global audience that the word “security” is the only prayer that still works in diplomatic company.

The question, then, is not whether Turkey and Damascus are secretly in love. The question is what happens to a minority community when multiple powers, for different reasons, decide it has had enough autonomy for one lifetime.

And in Aleppo, we are watching the answer being written. Not in the smoke. In the files.

THE ALLIANCE THAT WASN’T: A SUBCONTRACT DRESSED UP AS COMRADESHIP

There is a particular kind of betrayal that does not require malice. It only requires euphemism.

During the ISIS years, the West discovered the Kurds the way an empire discovers a tributary: with sudden admiration, strategic gratitude, and a vocabulary that sounded suspiciously like kinship. “Partners.” “Allies.” “Our most effective force on the ground.” The language was true in the narrow, operational sense. Kurdish fighters did what no press conference can do: they cleared streets, held ground, took casualties, and dismantled the caliphate’s grotesque little state one building at a time.

Yet the same officials who spoke that language were careful with every sentence that could be interpreted as a guarantee. The relationship was designed with an invisible ceiling. It was a mission, not a marriage.

From Washington’s perspective, this was prudence. The United States had no appetite for underwriting a Kurdish national project across four states. It had no intention of rupturing its NATO relationship with Turkey over Syria’s northern map. It wanted an anti-ISIS instrument that could take and hold terrain while American power remained mostly aerial, mostly remote, mostly deniable. A limited commitment, with enormous utility.

From Kurdish villages, towns, and neighborhoods, it felt like something else entirely. When you fight alongside the world’s most powerful military, when your dead stack up in a campaign celebrated in Western capitals, when your leaders are invited into rooms they were previously locked out of, you naturally infer that you have stepped into the shelter of a durable relationship. Ordinary people do not read footnotes. They read signals.

This is the heart of it: the West created a partnership that functioned like an alliance, was narrated like an alliance, and was experienced like an alliance by Kurdish communities, while being treated, legally and strategically, as a temporary transaction. Praise in exchange for performance. Victory in exchange for blood. Then a cooling of attention the moment the moral clarity dissolved.

The cameras, after all, are allergic to complexity. ISIS was a villain with a uniform and a brand. The defeat of ISIS could be told as a clean story of good and evil, coalition and liberation, women fighters and rescued minorities. What followed was murkier: border politics, Turkish veto power, uneasy Kurdish governance, Damascus reassertion, Russian games, Iranian militias, American hesitation. Murk cannot be merchandised. Murk cannot be watched in ten-minute clips.

So the Kurdish story returned to its traditional habitat: the margins.

This is why Aleppo should not be read as an isolated “clash.” It is a sequel to a much larger Western habit: outsource the dirty work, applaud the bravery, then behave as if applause is a substitute for protection. The West does not need to “forget” the Kurds in the literal sense. It simply needs to do what it always does when an ally lacks a domestic constituency: reprioritize.

And here is the brutal part, the part that should irritate even the most hard-nosed realist: this pattern has consequences beyond the Kurds. Credibility is a currency. It is spent by leaders in speeches and paid for by people with rifles. When it becomes clear that the West offers intimacy without guarantee, it teaches a lesson to every actor watching from the shadows. It teaches them that the fastest route to legitimacy is usefulness in the short term, followed by rebranding in the long term. Fight the right enemy at the right time, then wait for the invitations.

Which brings us back to Aleppo, where the Kurdish districts are being squeezed by converging powers, and where the West is once again watching through the wrong end of the telescope. The Kurds are praised in the past tense. The displacement happens in the present tense.

If you want to understand why this keeps happening, stop asking whether Washington “promised” something in writing. Ask what it performed in public. Ask what it signaled on the ground. Ask what it allowed Kurdish communities to believe.

Because the betrayal, in modern politics, often lives in the space between rhetoric and responsibility.

THE RETURN PHASE: WHERE DISPLACEMENT BECOMES POLICY

War has an aftertaste, and it is administrative.

The first act is loud enough to reach the camera lenses: shelling, street fighting, burning tires, the old choreography of panic. That is the part the world recognizes as conflict. The second act arrives dressed as order. It speaks softly, carries a stamp, and asks you to produce documents.

This is where the real verdict on Aleppo will be delivered.

You can call the January exodus a tragedy and still miss its meaning. Mass movement in wartime can be fear, improvisation, survival. It can also be something more deliberate: the creation of a new normal that feels accidental because it is achieved through routine.

The test is simple, and it is brutally unromantic:

Who gets to come back.

Not who tries to return. Who is allowed to return. Under what conditions. With what humiliations. With what paperwork that suddenly does not match the new rules. With what “security vetting” that behaves like a sieve designed to catch only certain names.

This is how states do demographic engineering without ever using the phrase. You do not need mass graves. You do not need televised expulsions. You can do it with checkpoints, with local committees, with selective detentions, with the quiet confiscation of property under the pretext of investigation, with the kind of uncertainty that makes people abandon hope voluntarily. A minority does not have to be driven out at gunpoint. It can be worn down until leaving feels like the only rational choice.

If you want to know whether Aleppo’s Kurdish districts are facing something like ethnic displacement, you do not begin with slogans. You begin with indicators:

Are returnees being detained in a way that disproportionately hits Kurdish men of fighting age?

Are families being required to produce impossible documents to reclaim homes?

Are there credible reports of property seizure, “temporary requisition,” or forced resale?

Is there a pattern of new residents arriving under the sponsorship of allied factions?

Do “security” files become hereditary, branding whole families as suspect?

In other words, does the state treat a neighborhood as a community or as a problem to be managed?

And this is where the story gets its most cynical twist: the same Western exhaustion that downplays the displacement will also downplay the return phase, because the return phase is boring to cover. It lacks drama. It is a slow grind of anecdotes that journalists struggle to verify and editors struggle to package. The bureaucracy is the weapon precisely because it looks like governance.

Meanwhile, the international conversation moves on to the next novelty. The world will be busy debating whether Islamists in suits are “pragmatists,” whether Turkey is “stabilizing,” whether Damascus is “reintegrating.” The vocabulary is soothing. It is the verbal equivalent of a sedative.

But the people in those neighborhoods do not live inside vocabulary. They live inside procedures. They live inside the question of whether their sons get stopped at a checkpoint and vanish into a holding facility with no charge and no timeline. They live inside whether their keys still fit their doors.

This is why Aleppo is not merely a Kurdish tragedy. It is a regional template being tested in a city the world no longer has the energy to feel sorry for. If the template works, it will be repeated because it is efficient. It produces control without spectacle. It allows diplomacy to call it “normalization.” It gives foreign governments a reason to shrug and say that at least the shooting has stopped.

The most dangerous sentence in this entire story is the one you will hear from respectable people, spoken with relief: stability is returning.

Stability for whom. Returning to what. Under which conditions. Those are the questions that decide whether a displacement wave is a passing crisis or a permanent rearrangement.

And those questions are rarely answered in the headlines.

ERDOĞAN’S KURDISH FILE: A DOMESTIC HABIT EXPORTED AS FOREIGN POLICY

To understand Turkey’s posture in Syria, start with Turkey’s posture inside Turkey. The Kurdish question there has been treated less as a political issue than as a permanent security condition, a kind of chronic fever the state has decided must be managed, contained, and periodically “treated” with force.

The pattern is familiar: elected Kurdish politicians sidelined by prosecutions, municipalities placed under trustees, civic space narrowed until ordinary political life begins to resemble probation. The point is not only repression. The point is deterrence. A minority is taught that every step toward autonomy triggers punishment, and that even legal participation can be reclassified as subversion.

Export that habit across the border and it becomes strategy.

A Kurdish autonomous zone in Syria carries two meanings in Ankara: a military risk and a symbolic infection. It is a sanctuary for armed groups Turkey considers extensions of the PKK, and it is a proof-of-concept. Proof-of-concept is what terrifies states. It tells people that alternatives can exist.

So Turkey does what regional powers do. It works the edges. It shapes outcomes without always owning them. It turns “counter-terrorism” into a solvent that dissolves every inconvenient distinction. Local self-rule becomes separatism. Kurdish self-defense becomes insurgency. A mixed neighborhood becomes a staging area. Language does half the work, then policy arrives to finish it.

This is why you see Ankara aligning, tactically, with Damascus’s interest in crushing pockets of Kurdish autonomy in Aleppo. The two capitals do not need affection. They share a target and a vocabulary. That is enough.

THE NEW SYRIAN RESPECTABILITY: ISLAMISM IN A SUIT, LEGITIMACY AS A COMMODITY

There is another transformation running alongside this story, and it has been handled with the delicacy of a magician palming a card.

Syrian leadership, fronted by Ahmed al-Sharaa, is being introduced on the international stage as a stabilizing necessity. Invitations appear. Sanctions language softens. The phrase “former” does a remarkable amount of laundering. Former this, former that, now a statesman, now a partner, now a man we must engage for the sake of order.

That rebranding has a logic. The world is tired of Syria being ungovernable. Diplomats are paid to prefer the attainable over the pure. NGOs need access. Governments want borders calmer. Everyone wants the shooting to quiet down so they can call it progress.

The cost arrives later.

When Islamist-rooted power acquires legitimacy as a governing product, it learns a lesson quickly: force plus patience plus a careful public tone can purchase recognition. The men with rifles discover the value of a press statement. The rhetoric moderates. The machinery remains.

Aleppo fits into this new respectability campaign. A state consolidating control over a major city can be sold as stabilization. A minority losing leverage can be filed under “security arrangements.” A mass displacement wave can be compressed into the bland word “clashes.” Then the conversation moves on, comforted by the illusion that governance equals justice.

WHY WESTERN MEDIA MISSES THE STORY THAT MATTERS

This is less about ideology in newsrooms and more about the physics of attention.

Aleppo has been suffering for so long that it has become a static image. A tragedy that repeats begins to look inevitable, and inevitability kills urgency. Editors chase novelty, and Kurdish suffering rarely arrives in a novel costume.

Access also matters. When reporting depends on intermediaries, narratives become easy to steer. Verification becomes hard. The return phase becomes invisible. Bureaucratic coercion rarely comes with video, and video has become the entrance fee for public empathy.

Then there is narrative fit. Kurdish displacement complicates the preferred scripts. It forces readers to hold multiple truths at once: Kurdish forces as effective anti-ISIS fighters, Kurdish governance as imperfect, Turkish security concerns as real, Turkish repression as systematic, Syrian state consolidation as predictable, Syrian leadership as newly normalized, Islamist pedigrees as inconvenient. Complexity is accurate. Complexity does not trend.

THE CONSEQUENCES THAT TRAVEL FAR BEYOND ALEPPO

The Kurdish story is always described as local. It behaves like a regional contagion of lessons.

Authoritarian states learn that demographic change can be achieved through procedure.

Militias learn that usefulness buys time, and time buys legitimacy.

Allies learn that Western praise is generous, while Western protection is conditional.

Europe inherits the downstream effects: leverage through migration routes, polarization imported through identity politics, cynicism toward liberal rhetoric that feels performative.

This is the part that should worry anyone who still cares about democracy as a lived practice. A system that speaks in universal values and acts in narrow transactions becomes easy to mock, easy to discredit, easy to manipulate.

And the people who pay first are the ones nobody has time to notice.

THE WATCHDOG LENS: HOW THE STORY GETS LAUNDERED WHILE IT’S STILL WARM

If you look at it with a trained eye for press framing, the first alarm bell is language. The second is sequencing.

The language is the softening agent. Whole political realities get dipped in it and come out presentable.

“Clashes” becomes the umbrella term that hides who holds the heavy weapons and who is running from apartment blocks with children. “Withdrawal” sounds voluntary, as if communities simply decided to relocate their lives for the sake of harmony. “Stability” arrives as a benediction, sprinkled over rubble like holy water. “Integration” is offered as an administrative inevitability, as if armed autonomy can be folded into a state structure the way a leaflet is folded into an envelope.

Sequencing matters because the moral meaning of events changes once the timeline is rearranged.

First you get a burst of violence. Then you get an evacuation. Then you get a handshake or a press line about calm returning. At that point, many outlets treat the story as finished. In reality, that is the moment the story begins. The return phase, the detentions, the property disputes, the selective permissions, the quiet intimidation that turns “temporary” into permanent: this is the part that rarely makes it into the wrap-up.

Media watchdogs have spent years pointing out a pattern on Middle East coverage: a weakness for romantic narratives of liberation, a weakness for tidy binaries, a weakness for treating Islamist repackaging as political maturation. Those habits can turn hard power into a misunderstanding and coercion into bureaucracy.

Aleppo exposes a related habit: moral attention gravitates toward spectacle. Kurdish suffering tends to arrive as attrition. Attrition makes poor television. Attrition makes excellent policy.

There is a further, uglier twist. Islamist-rooted leadership on a normalization path benefits from Western hunger for a “governable Syria.” When the world wants a story of order, it becomes willing to treat the victims of consolidation as an unfortunate footnote. A government learns quickly which sentences soothe foreign capitals. A government also learns which acts will be forgiven once the right sentences are spoken.

The net effect is a kind of moral money laundering: violence goes in, “stability” comes out, and the human cost gets written off as the necessary friction of history.

THE ISRAEL FILE: NEW INSTABILITY ON THE NORTHERN EDGE, OLD HABITS IN NEW UNIFORMS

Israel lives in a region where every “transition” comes with a receipt.

Start with the obvious: Syria is being repackaged as governable at the exact moment its governing class is still in the process of proving what it actually is. When an ex-insurgent apparatus becomes a state apparatus, it does not stop being an apparatus. It simply gains ministries, salaries, and a foreign-policy voice. That voice can be soothing in diplomatic English while the internal mechanics remain coercive in Arabic.

For Israel, this creates a familiar kind of uncertainty. The Syrian state may want calm for reasons of consolidation and international recognition. It may also be unable, or unwilling, to control every armed actor inside its own ecosystem. Those are two different threats. The first is strategic. The second is operational. Both can kill people.

Aleppo connects to this because Kurdish weakening removes a kind of friction in the system. Kurdish zones, whatever their imperfections, have functioned as obstacles to the free movement of certain networks, and as intelligence assets for those who cooperate with them. When those zones shrink, corridors open. Smuggling doesn’t need ideology. It needs space, incentives, and a shortage of accountability. Aleppo and its hinterland provide all three.

Then comes Turkey’s role, which is never only Turkish. A Turkey that gains leverage in northern Syria gains leverage in every conversation touching Israel, from Washington to Brussels to the UN. It can tighten screws quietly: influence over factions, control over border flows, narrative dominance framed as “counter-terror,” and a regional moral posture designed to flatter domestic audiences while pressuring foreign ones.

This matters because Turkey’s posture toward Israel has never been merely diplomatic. It’s performative. It is politics conducted as theater, and theater conducted with real levers.

Add to this the new respectability problem. Islamist leaders who are being normalized internationally learn an irresistible tactic: they can speak moderation in one register and tolerate agitation in another. One hand signs “stabilization” language. The other hand allows anti-Israel incitement to remain a low-cost domestic glue. That split-register politics is one of the oldest tricks in the region, and it works because foreign diplomats tend to read the English statements while local constituencies absorb the Arabic signals.

Now fold Iran into the picture, because Iran rarely exits a stage quietly. If the regime is weakening, three outcomes become more likely at the same time: desperation, factionalism, and adventurism. A threatened revolutionary state can decide that exporting chaos is cheaper than absorbing humiliation. Or it can lose control of parts of its proxy networks, which then behave with their own incentives and timelines. Either scenario increases volatility around Israel, regardless of whether Tehran’s long-run capacity is eroding.

Finally, there is the ISIS factor, the one Western audiences treat like a defeated villain who keeps showing up for sequels. ISIS doesn’t need to retake a capital to matter. It needs cracks. It needs neglected security seams. It needs rival powers squeezing each other so hard that nobody notices the basement door is open. Every reshuffling of authority in Syria creates those seams.

This is why the “Aleppo is local” framing is so misleading. A Kurdish neighborhood emptied in January becomes, by summer, a new logistics route, a new recruitment environment, a new intelligence blind spot, a new arena for deniable violence. States talk about sovereignty. Militias talk about resistance. Smugglers talk about profit. The consequences converge on whoever sits closest to the fault line.

Israel sits there by geography. It also sits there by symbolic gravity. In this region, Israel is never only a state. It is a screen onto which every actor projects a domestic narrative. That makes it the first target of the familiar bargain: normalize abroad, inflame at home.

And when you combine normalization with inflamed domestic politics, you get a particularly unstable compound. It looks like stability right up until it explodes.

THE EUROPE AND DEMOCRACY FILE: WHEN CREDIBILITY BECOMES A WEAPON USED AGAINST YOU

Europe likes to imagine the Middle East as a distant fire: tragic, recurrent, somehow separate. That illusion survives only because the smoke is intermittent. When the wind changes, Europe remembers that geography is not a theory.

Start with the most obvious lever: migration. Northern Syria does not have to collapse to produce pressure. It only needs enough instability, enough fear, enough uncertainty in return conditions, and enough local coercion to nudge families into motion. And once motion begins, Turkey stands at the tap. Ankara does not merely “host refugees.” It manages a strategic asset. Europe’s moral language about asylum meets Turkey’s transactional language about leverage, and leverage almost always wins.

Then comes the second lever, the one democracies are still learning to take seriously: propaganda.

When the West speaks in values and acts in bargains, its enemies don’t need to invent narratives. They simply compile the record. A partnership celebrated during the ISIS war becomes a “betrayal” story later, and betrayal stories are the currency of radicalization. Islamists use it to argue that the West is faithless by nature. Moscow uses it to argue that Western commitments are disposable. Tehran uses it to argue that America is a cynical empire. Each audience receives the version that suits its resentments. All versions land because they exploit a pattern.

The Kurdish case is an excellent exhibit. It teaches a lesson to every actor in the region, and not the lesson the West imagines it taught.

The intended lesson was: fight ISIS and you’ll have friends.

The learned lesson is: be useful, then expect abandonment, then plan accordingly.

“Plan accordingly” can mean building your own deterrence. It can mean turning to other patrons. It can mean making deals with extremists. It can mean adopting the habits of the brutal, because brutality is what seems to survive when promises do not.

This is how democracies lose the strategic advantage that is supposed to distinguish them: credibility. Credibility is not moral decoration. It is a form of power. It is the reason people take risks on your side. When credibility erodes, the world fills with actors who stop believing in law, stop believing in guarantees, stop believing in the patient work of institutions. They start believing in militias and patrons and revenge.

And this erosion does not remain “over there.” It comes home.

It arrives as polarization: foreign conflicts imported into European cities where identities are already contested, where social cohesion is already stressed, where social media turns nuance into treason. It arrives as cynicism: voters who no longer believe democratic governments mean what they say abroad, and therefore do not believe them at home either. It arrives as resentment politics: the suspicion that elites moralize while quietly bargaining, that they ask citizens for solidarity while practicing expediency.

It also arrives as a change in the internal logic of Western politics. Democracies are supposed to be restrained by law, by ethics, by public accountability. When voters come to see foreign policy as hypocrisy dressed as virtue, they become easy prey for demagogues who promise a simpler bargain: drop the pretense, take the loot, embrace the strongman logic openly. Moral inconsistency abroad becomes political corrosion at home.

This is why Aleppo matters even to readers who cannot place Sheikh Maqsoud on a map.

Because Aleppo is a test of whether the West can still conduct policy without teaching the world that power is the only language worth speaking.

And if it cannot, then the future belongs to the fluent.

EPILOGUE: THE PEOPLE WHO NEVER GET A “MOMENT”

Here is the obscenity of the Kurdish story: it is always important, and it is almost never fashionable. Other causes get their season in the spotlight. The Kurds get a recurring role in the background, praised when they are useful, forgotten when they are inconvenient, then rediscovered when the next catastrophe requires a brave minority to do the fighting.

Aleppo is not merely another Syrian episode. It is a warning label on a method.

Squeeze a minority. Call it security. Normalize the men doing the squeezing. Move on before the return phase hardens into permanent exile. Declare stability. Let the paperwork finish what artillery started.

If you want to know what this does to the region, watch the checkpoints. If you want to know what it does to Europe, watch the border politics. If you want to know what it does to democracy, watch what happens when citizens realize that “values” are sometimes deployed as campaign copy while “interests” do the governing.

The Kurds are not unworthy of attention. They are inconvenient to the stories we like to tell about ourselves.

So here are the only questions that matter now:

Who gets to return to Aleppo, and on what terms?

Who gets detained in the name of “vetting,” and who gets a clean slate?

Which governments will celebrate “stability” while quietly accepting demographic coercion as the price of order?

How many times can the West run the logic of subcontracted heroism before nobody shows up for the next war?

The headlines will keep sprinting. The Kurdish story will keep walking, carrying its luggage through the same corridors of history.

Pay attention to the people who never get a “moment.” They are where the region’s future is being decided.

Brilliant analysis of how displacement becomes policy through paperwork rather than spectacle. That point about the return phase being where demographic change actually gets locked in is something most coverage completely misses becasue bureaucratic coercion doesnt make for good video. Saw this exact playbook in other post-conflict zones where "vetting" turned into permanent exclusion. The credibility erosion you outline here isnt just a Kurdish problem, it becomes the template for every militia watching how partnerships with democracies actually end.